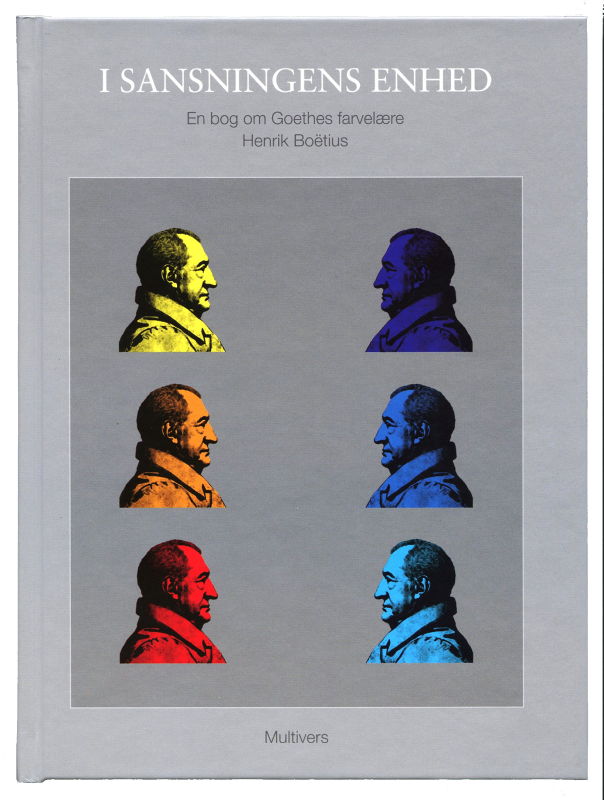

The publication I sansningens enhed (In the unity of sensation) presents and discusses Goethe’s (1749-1832) colour theory. It is an important theory, which many art students have studied and learned from, but it is often misinterpreted, says the book’s author, Henrik Boetius. With the book, he sets out to explain the theory and challenge some of the misconceptions the theory has been subject to over the years. Part of the reason for these misconceptions is that Goethe seems to have deviated from his own theory, the book explains.

‘Goethe’s ambition was to formulate a colour theory especially for the benefit of visual artists. His scientific insight is driven primarily by a strong intuitive grasp of the relationship between what we see, that is, the phenomenon, and the beholder. This intuition shaped his particular scientific method, which is rooted in a straightforward description of the world. Over the centuries, the theory has met with criticism, but today it is widely recognized,’ says Henrik Boetius.

Henrik Boetius is a senior lecturer at the Laboratory for Colour at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where for twenty years he has studied and taught Goethe’s theory of colour. In 1997, together with Marie Louise Lefèvre and Marie Louise Lauridsen, he co-created a film and a book about Goethe’s theory of colour called Light, Darkness and Colour, which were released in multiple languages.

‘In my experience, the nature of a colour affects us all in the same way, but we respond differently to it. The notion that “I love green, and you hate green” has nothing to do with the colour green and its nature but reflects how we as individuals relate to it, which is an entirely different matter. It seems that we all feel the impact of the colour but respond to it differently, and these individual responses reveal something about our personal characteristics,’ Henrik Boetius explains and adds,

‘To learn about the colour phenomena of the world from a personally detached perspective, as Goethe invites us to do in his theory of colours, we need to abandon our personal perspective in favour of a depersonalized perspective, which lets us see that the nature of a colour is a shared condition for us all. That is how we can learn about the response patterns that the personal encounter with the nature of colours evokes. The personal experiences that are generated when we work with the theory of colours hold the potential for a psychology of colour.’